A sermon on Matthew 22:23–33 and Acts 5:12–16 and for the Table United Church of Christ in La Mesa.

Two scriptures

If you’re like most folks at the Bible Study earlier this week—or maybe, if you were at the Bible Study earlier this week—you may have noticed something different about this week’s readings: there are two scripture selections, not one.

The first scripture we read is from the book of Matthew.

Each of the four gospels—Matthew, Mark, Luke and John—tells the story of Jesus from a slightly different perspective, a different angle.

Mark is lovingly known as the gospel for those of us with an Adderall prescription. It is fast-moving, colorful, full of run-on sentences. Mark was written the earliest and you can feel it, like it was quickly jot down as the story happened.

There are some historical and narrative hints that Matthew was written after Mark. It looks kind of like Matthew took Mark’s quickly-written-notes and said “cool, let me add some of the extra details I remember.”

Matthew adds in a number of direct quotes from Jesus that Mark just breezes right by, and Matthew adds quite a bit of theological detail to Mark—he adds commentary, whether implicit or explicit, about what the significance of Jesus’ life and death was for the way that people should think about God and their relationship to God.

One of Matthew’s more common theological perspectives is a placement of Jesus within second-temple Judaism. He highlights the moments when Jesus interacts with the sort of “influencers” of Jewish religious communities and discussing Jewish theology, and Matthew often kind of signals to the cosmic importance of Jesus teachings to Judaism as Matthew understands it. Matthew clearly wants his readers to see Jesus as not oppositional to Judaism, but deeply connected to it.

This week’s reading is a great example of that.

Heaven and hypotheticals

The Sadducees were a group of Jewish “influencers” who, importantly, did not believe in “the resurrection”—the idea that after death people go to Heaven.

Jesus was more closely associated with the Pharisees, another group of religious “influencers” who believed that when we die we are raised to be with God in Heaven.

The Sadducees pose a hypothetical question to Jesus: “so you believe in the fact that God resurrects people from the dead. You also believe in the law of God, given to us by Moses, which say that when a childless married man dies, the deceased’s brother should marry his widow so that his wife can still bear an heir. Say that happens, over and over, 7 times even, to a widow with terrible luck. Who is she married to when she goes to heaven?”

It’s possible to read this as a sort of “trick question,” and many people do.

I don’t like that reading for a few reasons, the most important of which is that it presents a picture of the Sadducees which is unfair.

We have no good historical reason to believe they were enemies of Jesus so much as interlocutors with Jesus: Jesus and the rest of the Pharisees and the Sadducees are people within one religious community debating about their own religion—we’re not yet at the part of history where Christianity is its own religion.

I read this more like the kind of hypothetical questions you hear lawyers pose when debating big constitutional ideas at the Supreme Court: if we decide to interpret the constitution in a way that conveys this right, does that conflict with other, existing ideas about the constitution? How would you resolve a tension between these two conflicting rights, if you really believe both exist?

Jesus responds by rejecting the hypothetical entirely.

“This hypothetical,” Jesus says, “does not account for just how powerful God really is. It operates on the assumption that all God can do is what you already know. That God works by the logic of this world. But God is much bigger than that. The structure of the Kingdom of Heaven doesn’t have marriage. Marriage is how we structure family on earth. We don’t need to structure family the same way in Heaven.”

The shadows of sent-out ones

The second reading is from the book of Acts. Acts is written something like a hero’s story, telling the history of the work of the Apostles—the “sent out ones.” The people to whom Jesus said “I’m about to leave and ascend to Heaven. It’s your job to carry the torch, go out into the world, and bear witness to the coming of the upside-down kingdom where the last are first and the first are last.”

The portion we’re reading here comes just as the book starts to pick up momentum, right before the Apostles go out beyond their home town of Jerusalem, and right before the first Martyr’s death.

We see the power of God present in the works of the disciples, in a way that feels a whole lot like how it was revealed in Jesus—in a way that hints to all around that God is still present and is revealed in the work of these disciples.

All kinds of impossible things are happening. The sick are healed. Those tormented with internal anguish are relieved of the voices inside their heads telling them lies about themselves and the world around them.

This reading includes one of my favorite lines in Christian scripture: “None of the others dared to join them” followed just 5 words later by “yet more believers were added.” You can almost hear the historian thinking “yeah nobody liked us… well I mean not nobody, we were very effective evangelizers!”

It’s not hard to imagine why both could be true at the same time, though—the Apostles are doing some kind of wild things, claiming to be working on God’s behalf, healing people… but also, they’re healing people! Impossible, unbelievable things are happening. It seems not totally ridiculous to me that they could both be experiencing mockery and be magnetically attracting people who needed healing the most.

Womanist readings

The two selection of scriptures this week—and the selection we’ll be using for all of the Easter season—come from the Reverend Dr. Wilda C. Gafney’s Womanist Lectionary.

If you’re unfamiliar with that language, “womanism” is a particular way of viewing patriarchal power dynamics through the lens of Black women. You might think of it as sort of a particularized feminism, centered not just on the experiences of women, but the experiences of Black women specifically. That’s not the whole picture—I’m significantly oversimplifying—but the important point for the time we have today is that Womanism centers the unseen among the unseen: Womanism says “the people who are oppressed by even the oppressed, their story and the story of how they respond to that oppression is what matters to us.”

Rev. Dr. Gafney—a renowned professor and priest in the Episcopal church—was bothered by the ways that the Revised Common Lectionary, the traditional schedule of scriptures read in mainline churches, just kind of glosses over, skims past the stories of women and particularly women from historical minorities in scripture.

She was tired of the ways that women’s stories—positive or negative, traumatic or healed—just aren’t told in mainline churches. So she organized a new lectionary, with new scripture selections, that force us to reconcile with and explore women’s presence in Christian scripture.

If you’ve never heard this portion of the gospel of Matthew before, that’s not a surprise to me. It appears nowhere in the Revised Common Lectionary. You could go to a mainline church your entire life and never hear this interaction between Jesus and the Sadducees.

I can’t tell you I know why that is, but I can say that what Rev. Dr. Gafney did here is important.

At Bible Study on Tuesday, I was touched by how quickly folks caught on to what’s unique about this passage: the hypothetical in this story is not just a hypothetical about resurrection. It is a hypothetical that pre-supposes a patriarchal world where a woman’s job is to bear an heir for a man—even a deceased man to whom she is no longer married!—at just about any cost, even if it means being transferred from husband to brother-in-law to brother-in-law seven times over, like a family recipe book or trading card collection or something. Like property.

I can’t say that I know Jesus was thinking of this when he spoke about there being no marriage in Heaven, but when I read this passage with Rev. Dr. Gafney’s intentional, womanist selection of scripture in mind, I’m struck pretty quickly by what there being no marriage in Heaven would mean for this woman.

In heaven, something she may not even dream of as possible on earth happens: she is no longer subject to any man. None of the seven men who have treated her like property have any power over her anymore. Family is structured differently, without the power dynamics it has on earth. She is like an angel.

The resurrection is not just about no longer being physically dead, it is about no longer being physically constrained, about a brand-new way relating to one another.

The power of God that Jesus said his interlocutors did not understand was not just about God being the Monarch of Heaven, but about God’s power to rule that Heaven in a way that is far different and better than we could ever imagine.

Healing before heaven

There is one thing that still bothers me about this, though: I can’t help wondering whether the widow in the hypothetical would see a promise of a liberated afterlife as a complete comfort for her immediate, present status as the property of her late husband and six late brothers-in-law.

Her life on earth, right now, is colored by her experience of being unseen. Waiting for the hope of heaven might help but it doesn’t heal—it doesn’t stop the present bleeding.

If God, as Jesus said, is the God of the living, what about the living widow? Does she need to wait until a second life before she can be saved?

I wonder if we might find something for her in the scripture selection from Acts. The thing that happens after Jesus dies, is resurrected, and leaves the Apostles to continue his work.

In that scripture, we see another impossible thing happen, another flipped power dynamic.

The Apostles bring “signs and wonders”—acts which are supposed to evidence that they come on behalf of God. And the evidence, in this case, is not fire raining from heaven or a spring rising in the desert, but the healing of mental and physical illnesses.

In a world without the Americans with Disabilities Act and without disability theorists helping us see how society can offer liberation to disabled people by creating a more accessible world, I imagine the impairments these folks had would be especially ostracizing—maybe even more than they are today. It might be particularly hard to participate in community life.

I bet that it felt for some people like the only way they would be treated as equals would be if their illnesses or impairments were gone.

But what an impossible idea that would be—blindness you had lived with your whole life in a world that ignores the blind, suddenly disappearing?

But God is the God of the living, and God’s presence among the apostles is revealed in the liberation of the oppressed—the kind of liberation that many may have never thought remotely possible.

Finding heaven while looking for hell

But what about today?

We do not generally see people experience miraculous physical healing at church today. Paralyzed folks don’t ask friends to bring them to church so that they might catch Pastor Kelly’s shadow.

What ways is God’s impossible liberatory work happening today?

When I think about that question, I think about the journey that brought me to the UCC.

I’d been going to this fundamentalist church that had a pretty exclusionary posture towards gay people, and while I didn’t have time to put on my glitter nail polish this morning, I am indeed quite gay.

I spent so much time in that community trying to cure my own homosexuality so that I could belong, so that I could be someone who they saw as “right with God.” I’d spent 9 or 10 years following destructive practices that promised to rid me of my attraction to men. But nothing worked. And it wore on my soul.

One week, though, I just knew I needed something different. I figured I was destined for hell, whether I went to the more exclusionary church or not, and if I was going to go to hell, I might as well go down without the mental anguish along the way. I’d go down singing.

So I searched on Google “gay church near” and my zip code, saw the nearest one was Kensington Community Church, and told myself I’d visit just once. I prepared for the place to feel just disgusting and repulsive, to be surrounded by all the things I’d spent the past decade running from. I was prepared for hell.

What I found instead, though, was an abundance of God’s love, poured out among the people. It was heaven.

I found folks older than my grandparents accepting me and offering unconditional love and acceptance to me that my natural grandparents never would be able to. I found affirmation that God loved and accepted me not in spite of my being gay, but inside of and because of it.

Resurrection even for my enemies

I think, also, about the time I “came out to” my fundamentalist church as a celibate gay man. This was a couple years before I joined KCC. I’d decided I couldn’t not be gay, so I’d just be celibate, and I told my story at church.

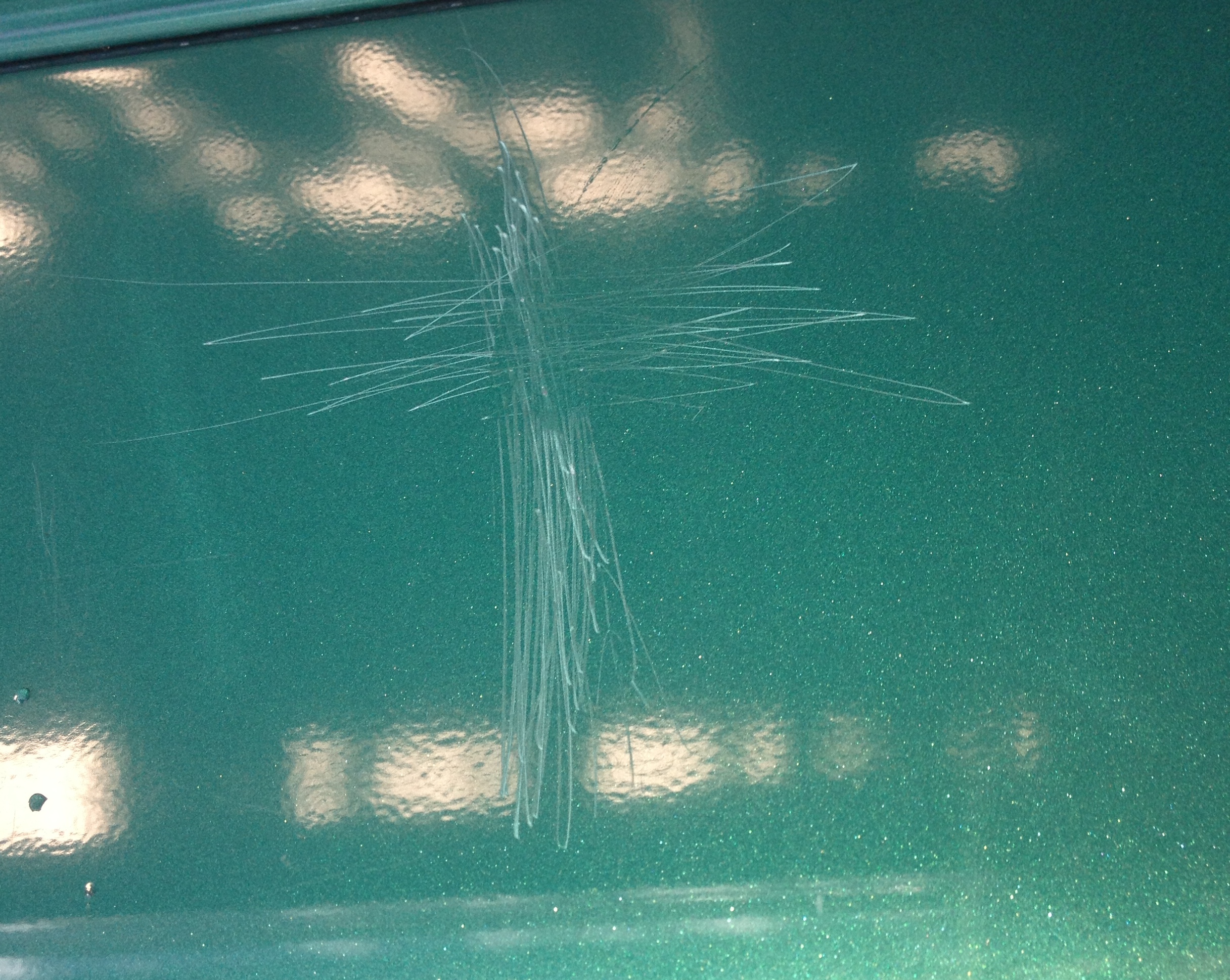

Shortly afterward, I was leaving a church event, and came out to see my car keyed all over the hood and both sides.

On the hood, in letters about as tall as my forearm, read a six-letter homophobic slur, and all over the rest of the car were etched crosses—something I couldn’t help but read as implying this message came on behalf of Jesus.

I tried to ignore the hurt, but I couldn’t. And I suppose I don’t know that it was actually someone from church or someone who knew that was my car or that it happened because of my coming out. I never really investigated all of that. But it happening at a church event hurt all the same.

And the pain was pretty unavoidable. I had to face it every time I walked out to my car, every morning when I made my 5 am commute I’d see “F, A, …, …, …, T” confront me as I walked up to my car. Every time I opened or closed the driver-side door, I saw the etched cross. It felt like death.

This went on for a month or so, and at the time I was a broke college student. I had no idea when I’d be able to afford to repair my car.

Then someone at the church—this brand new guy who’d been coming for only a few weeks—saw my car, told me he was a painter, and that even though he didn’t paint cars he did do airbrush work and was great at color matching, and offered to clean up my car for free. Free.

I cannot tell you how liberating that felt, and how much hope it gave me that this community could learn to offer love to people like me—even if I had to leave before they could grow in that way.

The shadows of sent-out ones (revisited)

There’s this meditative song I really love, Let You Go by United Pursuit. It’s all about releasing ourselves from the limits we put on God.

Maybe my favorite verse—the one I could listen to on repeat over and over if I had to—goes like this:

When the way is unclear and the answer’s illusive

He is different, by far, than our broken conclusions

You are not the God my pain has conceived

You are deeper and stronger than my eyes can see

And as we prepare to wrap up for the day, I can’t help but offer one last wondering:

When we bump up against an unclear way, when we see a challenge that is unsurmountable, how do we remind ourselves that we worship the God of the living?

When and where and how do we remind ourselves that a better world is possible even when it seems impossible?

When and where and how do we seek out the limits we place on God and rid ourselves of them?

How can we find the ways God is at work today? And how can we show it?

When someone walks in our shadows, do they see that we are sent-out ones?

I will not pretend to know how we do all that? But I do know it requires justice work, it requires the repair of harm done both to us and to our neighbors by us.

I know it requires the kind of repair work that is done by repainters of keyed cars and by surrogate grandparents. I know it requires protests and peaceful action.

And I know it’s something we can only do together, as God’s church, as the “sent-out” ones.

Amen.