A sermon on John 11.17–21 and Acts 11.1–4,10–12, for The Table United Church of Christ in La Mesa, California.

John the oddball

This week’s gospel reading starts right in the middle of John.

John is the most “different” of the four gospels.

Matthew, Mark, and Luke tell stories of Jesus that overlap greatly; they tell very similar narratives from slightly different perspectives. You might imagine that those gospel writers stayed good friends and were building on one another’s memories.

John’s gospel was written down potentially as long as a generation after the first three, deeper into the time when Christianity separated from early Judaism and became a religion of its own. Folks’ ideas about who Jesus was had started to form a little more. The gospel introduces Jesus as the “word,” the logos, the foundation on which the earth is ordered. John tells a more victorious, and less tortured, story of Jesus. I’d imagine that another generation after the death of Jesus, it might be easier to remember how the story ended, that memories of Jesus would be less traumatic because they’re remembered not by those who witnessed the brutality of Jesus’ treatment, but by those who have grown up hearing about the power of his resurrection to turn the world upside down.

This story happens right smack in the middle of John, where Jesus is walking around and teaching and performing miracles. Jesus is busy, at work, doing things that reveal himself to be God.

This particular story is told only by John; the other three gospel writers do not include it in their narratives—although, as you may have heard whether in church or in pop culture, Mary and Martha do make an appearance elsewhere.

Mary and Martha in Luke

In Luke, there’s this story where Jesus comes to town and he’s being hosted by Mary and Martha.

Martha, famously, is quite the homemaker. She’s a diligent host who works hard to make sure Jesus feels welcome. Cleaning, cooking, setting the table, that kind of stuff.

Mary, on the other hand, is too busy spending time with Jesus to worry about serving Jesus.

When Martha senses the authority Jesus has, senses that Mary would listen to anything Jesus said, she tells Jesus “hey, tell Mary to come help!” but Jesus says “no, no, I don’t need the table set, I need you to spend time with me.”

Then there’s the account in the book of John.

Mary, Martha, Lazarus in the book of John

Just before the story we read today, Jesus hears word of Lazarus’ sickness. Folks come to tell Jesus, “hey, go see your friend, he’s sick,” but Jesus says “not right now, I’ve got work to do, I’ll head over in a bit.”

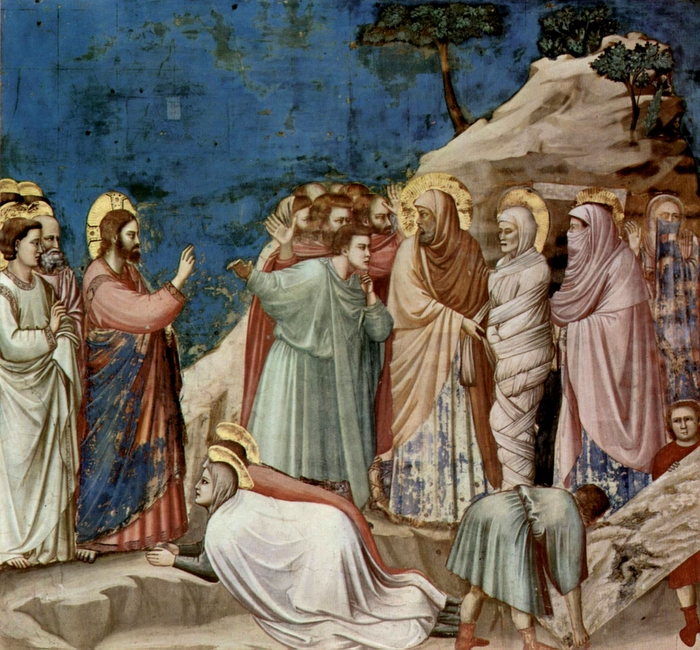

That’s where today’s reading begins. Jesus arrived in Bethany, the place where Mary, Martha and Lazarus lived, and is told that Lazarus is no longer sick—he’s dead. He’s been entombed for four days.

Martha hears Jesus has come into town and she goes over to meet him. “Teacher,” Martha says when she sees him. “If you had been here, my brother never would have died.”

What a heavy sentence to read. I hear Martha say that and I hear a mix of pain, of sorrow for what could have been, and maybe a disappointment or an anger towards Jesus… where was her teacher when she and her brother needed him? Where was her miracle-worker when she most needed a miracle?

But then Martha goes on. “Even now I know you have great power and God will do as you ask.”

I hear that and I hear a kind of cautious optimisim. A belief that Jesus is powerful, even if that belief isn’t ready to name the specific powerful thing she’s asking Jesus to do.

“Your brother will rise,” Jesus says back. My gut instinct, when I first read this, was to see this as Jesus telling her “I am going to raise your brother from the dead. Don’t worry, friend.” It turns out my gut instinct was missing something important, though: the International Critical Commentary—a peer-reviewed collection of linguistic and historical analysis of scripture—tells us that this was a common consolation for the grieving. Something like what how we might say “she’s with Jesus now,” or “your grandma is watching over you in heave” these days.

While it’s possible Jesus had a deeper meaning than the token consolation, it doesn’t appear that Martha would have had any reason to see that meaning.

Martha affirms this, saying back, “yes, I know he’ll rise on the last day.” “Yes, I know I’ll see him in heaven.”

Then Jesus says, “I am the resurrection and the life.” I’m here. You are my people and you have nothing to worry. Everyone who believes in me will live. Do you believe this?”

And Martha, importantly, does not affirm the “this” to which Jesus refers. Martha says “Yes, I believe that you are the Messiah, the Son of God, the one who comes into the world.”

Jesus says “do you believe I have the power of the resurrection, right here, with me right now,” and she says “I believe you are the Son of God,” back.

I thought of that this week and I thought of when a new partner says “I love you” for the first time, and the words come with so much weight that you can’t quite ignore them, but you also maybe aren’t ready to say it back. So you affirm them, but don’t repeat those words. You respond with a smile, maybe a kiss, a “you’re the best thing to ever happened to me,” an “I love spending time with you,” but not quite an I love you. That feels too heavy.

Maybe “I believe you can raise the dead” feels too heavy for Martha right now.

And that’s where this week’s reading cuts off. A few verses later, Mary has an interaction with Jesus that’s somewhat different, but still does not end in her explicitly believing Jesus will raise her brother from the dead.

We know how it ends—we know Jesus resurrects Lazarus a few verses later. But if we imagine ourselves as Martha in this moment… Martha just knows her brother is dead. And that’s the most real thing to her right now.

She doesn’t seem ready to believe Jesus will actually raise her brother from the dead. At least, not yet—that’ll come later.

Acts

Then we have the reading from Acts. While last week’s story was way at the beginning of Acts, while the Apostles were still in Jerusalem, this week’s reading is way towards the end. The apostles are out, traveling around, telling the story of Jesus, the savior and liberator, who defeated death to anyone who will listen.

The first folks they talk to, in Thessalonica, are somewhat receptive. Some of the people in the synagogue believed, as did many Greeks, and a few prominent women.

I have to confess, sometimes when I read this part of Acts, I get a little… embarrassed. Paul and Silas are like, street preachers here. At least aesthetically, they’re those folks shouting Bible verses outside Padres games. But that’s the kind of thing that happens when you have a big transformative experience like Paul did. You start shouting about it.

Of course some people will be attracted by that—and of course, only some. That won’t work for everyone.

Then they go on to Berea, and the people there are “high-born,” and “open-minded,” moreso than those in Thessalonica. That word “high-born” could sound kind of elitist, but contextually it reads more like “educated.” These are the folks with PhD’s and you can see it because when they hear the word of Jesus, they were eager… and their eagerness leads them to test the story that Paul and Silas are telling them. They examined the scriptures, see if what Paul is saying makes sense, and then believe. The highly-respected Greek women and “more than a few men” believe.

Four groups

Between this week’s readings, I’m noticing something like four groups of people who believe in and follow the story of Jesus.

First, there’s Martha and Mary. They’ve seen Jesus in the flesh, known Jesus, loved Jesus, and they believe quite big things about Jesus. They just aren’t ready to believe he’s going to raise their brother from the dead.

Then there’s Paul, who though he did not meet Jesus in the flesh, had a huge transformative moment where he met Jesus in the spirit, something transcendent and special that literally changed the way he saw the world. And he believes in the resurrection.

Then we have the folks in Thessalonica. They hear Paul and Silas preach, and at least some of them believe instantly. There’s no “inspection” happening. They hear the message, are attracted to it, and believe.

And finally, we have the folks in Berea, who hear the message and say “hmmm, let me dig deeper,” evaluate the scriptures for themselves, and believe the whole thing.

Two groups of people who have seen Jesus firsthand: one that believes instantly all the biggest things possible about him, and one that is a little trepidatious when it comes to believing the whole “rise from the dead” thing.

Two groups of people who hear about Jesus secondhand, one that believes instantly and one that believes after a little research.

What do you have to believe?

In Bible study this week, folks quickly got to asking a bunch of big questions about belief.

- What does it mean to believe in Jesus?

- What do you have to believe to be saved?

- And what are we saved to or saved from—what does it mean to be saved if we believe?

- Do we have to talk about all this resurrection stuff, even when it kind of ruins the “brand” and makes it hard for some of our friends to come to church?

For some of us, those answers were easy. “Of course I believe in the power of Jesus to resurrect from the dead!”

For others of us, those answers were harder. “Do I really have to believe in the bodily resurrection? Can there be more complexity to my beliefs?”

And if we’re honest, some of us had very strong words for folks who believed different than us—who were confident in the bodily resurrection, or who were confident that bodily resurrection could never be.

I must confess, folks, I was sweating bullets. Sitting in my home office, on Zoom, all I could think was “thanks, week 2 here and you’re already making me confront the hard ones.” I started texting my clergy friends like “hey uh, so… what is the official answer to that?”

These are not simple questions to answer.

The not-so-simple quality of these questions comes in part because we are not a monolithic church—neither we at the Table UCC La Mesa, nor in the United Church of Christ broadly, nor in the Church universal.

Christians, after all do not all believe the same things, and do not all come about that belief in the same ways.

Nicean boundaries

There have been attempts to unify Christianity around a very specific set of beliefs for at least 1700 years. Some of those attempts have been more successful than others, but the fact that there exist 200 denominations should hint to you that none have completely succeeded.

The current most popular boundaries of Christian belief can be found in the Nicene Creed. You’ve probably heard of it before.

It starts like this:

“We believe in one God, the Father almighty, maker of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible.

We believe in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Only Begotten Son of God…”

The whole thing is 224 words long and I will not pretend to have it memorized — I did not exactly get a perfect score on my “creeds” exam.

The Nicene creed does indeed include some of the most unifying beliefs in Christianity. Most Christians can probably read it and go, “yep, I’m in that ‘we’ who believes in those things.”

There is a ton of diversity on the matter, but as a general rule, folks in our tradition do not generally lean on the creeds—including the Nicene Creed—the way some other do. You may have heard them described before as “not tests,” but “testimonies.”

While our church broadly testifies a belief in the contents of the creeds, we do not accept those creeds as a test of Christianity.

We do not see them as the boundary for who is in and who is out. We do not require you to initial each line if you want to become a member.

There are a good many reasons for that—our community values freedom of conscience in a way that would be hard to square with a test of faith like that, for example. But maybe one of the most important reason to reject the creeds as tests of faith, at least in my view, is because the first Christians—the ones who started it all—would have failed that test.

Christianity, after all, existed before the creeds.

Christianity before the creeds

Christianity was not invented in the year 325 of the common era, when the Nicene Creed was written and agreed upon.

Rather, for the first 300 years of our faith, Christians were bound by something else: by the sacraments of holy communion and baptism.

We were united not in the split hairs and specifics of what we believed, but in what we lived—in how we united to one another in sharing the Lord’s Supper, how we welcomed each other into the community of faith with baptism, and how we pursued Jesus’ upside-down kingdom together.

They knew what one of my favorite authors, Rachel Held Evans, knew when she wrote that Christianity “isn’t meant simply to believed, but to be lived. To be shared, eaten, spoken and acted in the presence of other people.” To do the things we cannot do alone.

And that is still true.

And I, at least, am grateful for that. I am grateful for a Christianity that is not a test, but a testimony.

Here’s why:

If there is a God…

Five weeks and nearly 3 dozen mass shootings ago, the poet Kashif Andrew Graham posted this poem on Instagram.

“suffer the little children

to come unto me”

They are unto You,

now what?

if there is a god, may god

hurry up the day

when guns are loaded

up behind thick museum glass.

Why is it normal for

bullets and bulletin

boards to live in the

same sentence?

and if there isn’t a god,

hurry up the day when we

crown ourselves responsible,

when thoughts smack

like a gavel, and prayers

are speeches given before

we break broken [shit],like children.

Kashif Andrew Graham, @kagwrites on Instagram

In a week when there have been so many mass shootings that the website of the nonprofit which catalogues mass shootings in the US—the Gun Violence Archive—went down as people all over the country tried to keep straight the number of deaths and injuries that resulted from our gun culture… in this week, that poem is extra painful to read.

It’s painful, in part, because it is honest. It makes the same honest lament that Martha does in this week’s scripture reading—“if you had been here, my brother never would have died. “If there is a God, why won’t God hurry up and fix this. If God were really here, wouldn’t God have stopped the murder of children?”

Like Martha, it offers a belief that is not without reservation.

And as with Martha, I can’t hold those reservations against Kashif.

I can’t see myself telling Kashif, “no actually, you don’t get to worship with me because you do not believe like I do.”

I would much rather say “Kashif, Martha, come to the table with us and stay as long as you like. Come live with us, whether or not you’re comfortable signing the same creed as us.”

And I’d like to say the same to you.

Whether you are a Martha, who believes big things about Jesus, but is not about to presume the bodily resurrection,

Or a Paul, who had a transcendent experience and instantly believed the most fantastical stories,

Or like the Christians in Thessalonica who merely heard the story of Jesus and instantly said “that’s the most true thing I’ve ever heard,”

Or maybe like the Berean, who believe the most fantastical things but only after hard-fought battles of the mind,

Come.

Come anyone in this room or online who is interested in something to live, not just something to believe; anyone who drawn to the story of Jesus and to the community of people who follow him.

Come as we joyfully share in bread and wine and water and Spirit.

Amen?