A sermon on Genesis 12.1–4 and John 3.1–17, for Kensington Community Church in San Diego.

Parallel calls

Our two passages this week tell stories that take place two millennia apart, but have something important in common.

The first reading, from the Hebrew Scriptures, tells the story of Abraham’s call from God.

Go out from Babel

In the chapter before this one, the author of Genesis recounts the story of the tower of Babel. God had commanded the descendants of Noah, post-flood, to spread out and fill the earth. God didn’t want folks clumped up and stuck in the place where their boat landed; God wanted them to explore creation, prosper, expand.

But the people did not want to do that. They wanted to stay close to home, close to comfort, after the trauma of the ark and the flood. They huddled up close, built a city together, with a magnificent tower that they called a monument to themselves.

And God said no—no, no, no. We can’t have that. You need to break out of your comfort zones, leave the city, and fill the earth. Because the people wouldn’t listen, God kind of forced their hand. The scripture says God said “let’s go down and mix up their language so they won’t understand each other.” Suddenly, people don’t all speak one language, and naturally, they break into language communities and start spreading out among the earth.

I can only imagine how jarring that must have been—to be speaking the same language as your cousin one day, and then the next, to not understand each other, and then to have to leave your family and find folks who talk like you so you can get by.

As a result, it appears there was a rift in the relationship between God and humanity. For 10 generations, there is no record of the two speaking to one another.

Abraham hears from God

Then Abraham is born, and 75 years of Abraham’s life later, he hears from God.

There is no context, no preface, to this. The text just jumps straight from the genealogy of the 10 generations of silence into “The LORD sad to Abram.”

The command God gives Abraham is not too different from the command God gave the folks who built the tower of Babel: go out. Leave your home.

The Hebrew scholar Naham M Sarna notes that there’s a crescendo that happens when God tells Abraham to “go.” God lists all that Abram would be leaving behind in increasing intimacy, increasing seriousness. “Leave your native land, leave your extended family, leave your father’s house. I am taking you somewhere new.”

Quite a big ask, considering all Abraham has to go on is a promise from a God who had been silent since long before Abraham was born.

If I’m totally honest, I can’t imagine that I would obey that kind of a command from God.

I don’t know that I would be that brave.

But Abraham was.

Abraham left his home, left his comfort zone, started fresh, and ended up fathering the Israelite people, and a total of nine religions that claim Abrahamic roots.

Come away with me

This made me think of a song I used to sing at church, Come Away.

Come away with me

Come away with me

It’s never too late,

It’s not too late,

It’s not too late for you

I have a plan for you

I have a plan for you

It’s gonna be wild

It’s gonna be great

It’s gonna be full of me

I hadn’t listened to that song in a good while.

I think it’s because I used to think of it as a song that was about like, God forgiving all your mistakes and letting you move on, and that’s just an element of theology that isn’t terribly interesting to me anymore.

But this week I heard the song in a new light. It was “born again” to me, like I was hearing it for the first time.

I heard it as the voice of God saying “it’s never too late for me to do something new.”

“Come away with me,” Abraham. “75 years old? You’re still spry enough to walk the dessert. I’ve got fun plans, come with me.”

A song about absolution of guilt, reborn into a song about a chance for something new.

I thought about all the queer and trans youth on coming out—or maybe “coming away”—journeys, and how many of them pay an unfair cost for it.

LGBT+ youth experience homelessness more than most other demographics, with nearly 40% of homeless and runaway youth identifying as LGBT+— the majority of them citing family rejection as the primary reason why.

When you’re coming out, it’s hard to know what the future holds. Many queer and trans young people describe being unable to imagine their lives in adulthood, unable to see what will happen when they come away.

And maybe that—plus recent social developments that make things somewhat safer—is why we also see so many folks waiting until late in life to come out as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender. It’s hard to be something you can’t see.

But it’s never too late. We hear the whisper in our heads:

Come away with me

Come away with me

It’s never too late,

It’s not too late,

It’s not too late for you

LGBT+ folks come away, often regardless of whether they can see what the road ahead will actually look like regardless, and when they do they discover the beautiful life God has in store for them, a life that’s great and wild and full of divine joy.

Then we get to the gospel reading.

My carry-on baggage

If I’m being totally honest, the gospel reading is one that I come to with a lot of baggage.

First, there’s my personal baggage with the passage: I must have read this passage more than a thousand times before, when I was practicing a much more exclusionary approach to Christianity.

John 3:16 was my favorite verse as a kid. I think it was the first one I ever memorized.

“For God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son so that whosoever should believe in Him would not perish but have eternal life.”

For years, I thought I knew exactly what that passage meant: that each human being had racked up a debt of sin against God.

This debt meant we were all bound to go downstairs and not upstairs when we die, if you know what I mean.

But God loved us so much that God erased that debt by making his Son pay for it instead of us.

Those who believed the same way as me—and only those who believed the same way as me—would receive the benefit of that debt payment.

And I must confess, even as I left behind that theological perspective, I didn’t totally leave behind my association of this scripture with that perspective.

As I researched the scripture, I kept beginning to read commentaries and academic literature about the text… only to wind up closing the book or the PDF after a few pages.

I kept finding myself doubting the authors’ ability to disprove my presuppositions about the passage after only a few readings.

I was—albeit subconsciously—using my old theological perspective as a zero point, forcing those authors to reconcile with my history, to compare themselves to the past I wasn’t quite ready to leave behind.

I wanted change, but something inside me was too afraid to actualize that change.

I was stuck.

I figured maybe I could get out of dealing with my personal baggage by focusing on another kind of baggage this package comes with: interreligious interpretive baggage.

Interreligious interpretive baggage

The Gospel of John is sometimes called an antisemitic text, and I understand why folks—especially Jewish folks—feel that way.

John was written in the midst of the church’s contentious separation from Jewish community. Christianity was just starting to be called Christianity; the church was just starting to be understood as something more distinct than a set of unorthodox beliefs held by some folks within other religions—mostly within Judaism.

Compared to other gospels, John presents interactions between Jesus and the people of Jerusalem as particularly oppositional. That oppositional posture gets quite pointed when it comes to influential people within Judaism, including the Pharisees, who would go on to become the forebearers of modern-day Judaism.

Terrible interpretations of John have left some contemporary Christians blaming Jewish people for the death of Jesus. Antisemites love to quite John for all the times they’re able to connect the dots between “the Jews” and Jesus’ death.

Further terrible interpretations mistakenly understanding the Pharisees to be a group of particularly unkind, rigid, and restrictive leaders who were married to an old temple system that Jesus comes to destroy.

But while the gospel of John certainly documents real tensions between Judaism and the teachings of The Way of Jesus, the antisemitic interpretations don’t quite hold water for me.

For one thing, the totality of scripture suggests that if we’re blaming anyone for Jesus’ death, it might be the Roman Empire… although even that is doubtful to me. In the apostle Paul’s epistle to the Galatians, we’re told that Jesus gave himself. In today’s gospel passage, we’re told God gave God’s only Son.

For another, the gospels are full of loving relationships with Pharisees. We see, throughout Jesus’ teachings, evidence he studied with the Pharisees. The Pharisees were not a powerful elite, but a devout group of scholars, worshipping the same God Christians believe to be revealed in Jesus, who were just as oppressed by Roman occupation as anyone else in Jerusalem.

But the poor interpretations remain.

And I think if we want our scriptures to not be known as antisemitic, it’s our duty to ensure they are not interpreted in an antisemitic way.

Take this week’s gospel passage, for instance.

Ragging on Nicodemus

Many people observe this text in a way that paints Nicodemus as weak, too ashamed of his attraction to Jesus’ teaching to come by day, and sometimes too cerebral to understand the artful speech of Jesus.

One Christian blogger says Nicodemus was “a tepid, tiny follower of Jesus at best.”

Tim Keller, pastor of Redeemer Presbyterian in Manhattan—whose books I have a whole collection of!—described Nicodemus as a model for us to follow… but only because he has set aside his “Pharisaical” ways to follow Jesus. Nicodemus is a good guy, to pastor Keller, in spite of his status as a Pharisee, not inside of it.

Insistent on finding a more positive message, I turned to probably one of my top two most beloved theologians, Robert Goss. Unfortunately, I found that he, too, engages in this kind of ragging on Nicodemus.

In his contribution to the Queer Bible Commentary, Robert Goss describes Nicodemus as being like a closeted priest dealing in homophobia by day; willing to explore his true desires only under the cover of night, and only in shallow ways.

Even when Nicodemus is unambiguously supportive of Jesus, he can’t catch a break from theologians.

Nicodemus will appear two more times in John’s gospel.

On one occasion, he defends Jesus before the high court, without Jesus or anyone else pleading for him to do so.

The final time Nicodemus shows up in the gospel of John is even more special: after Jesus’ death on the cross, Nicodemus joins Joseph of Arimathea—another Pharisee!—in ensuring Jesus has a dignified burial. Nicodemus personally brings 75 pounds of myrrh and aloes to bathe Jesus’ dead body in, the kind of thing you do for a king.

And yet, church father John Chrysostom responds to the story by implying this all was actually a bad thing, that it indicated Nicodemus and Joseph must not have been sufficiently confident Jesus would be resurrected.

“They brought spices which are most likely to preserve the body for a long while,” Chrysostom writes. “A procedure which indicated that they thought nothing out of the ordinary of him.”

No thanks, Nicodemus. You’ve brought the wrong gifts.

Maybe it’s just the personal baggage I was bringing along for the ride, but it was starting to feel like no one could read this passage without it being some sort of an us-against-them story. I couldn’t seem to find a way to square this circle, to interpret this passage in a way that was faithful to the text without dishonoring my Jewish neighbors.

I was stuck. Again.

2 pm on Saturday

After weeks of wrestling with sources, I found myself at 2 pm yesterday with nothing written down. Whoops.

I put all my reading materials aside, sat still, and turned on my meditation playlist.

Eventually, it got to a song I’ve enjoyed since college—Climb, by Will Reagan and United Pursuit. The song goes like this:

I lean not on my own understanding.

My life is in the hands of the maker of heaven.

I lean not on my own understanding.

My life is in the hands of the maker of heaven.

After a minute of this, the refrain changes to:

So I will climb this mountain with my hands wide open

I will climb this mountain with my hands wide open.

As the song played, I couldn’t help but think about how much my hands were not wide open in that moment.

They were full of the baggage of sixteen centuries of interpretation that I no longer wanted to abide.

I thought about how “my own understanding”—and on behalf of Christianity, our own understanding—was keeping us from seeing something beautiful and new in the text.

Renewing my relationship to the scripture

But how could I get past that? How could I open up my hands to something new?

I flipped to a blank page in my notebook, prayed for fresh eyes, and reread the scripture. I tried my best to look at the text without any of my presuppositions, imagining I’d never heard of or read it before.

I found myself asking a whole different category of questions.

Instead of wondering whether Nicodemus was the good guy or the bad guy, I spent my time wondering…

- Who is the Human One?

- What is “belief” here? What does it mean to “believe in” God’s Son? Like believe that he exists?

- What does it mean to be Born of the Spirit?

- When Jesus says “we speak about these things,” who is the “we?”

- What’s all this about God giving God’s son? How do you give a child?

- How is the world “saved?” What is it saved from?

I grew compassionate for Nicodemus.

Instead of seeing Nicodemus as the homophobic pastor who betrayed his own cause, I saw Nicodemus in myself, just after I’d come out, falling in love for the first time and carefully tip-toeing into the shore waters of this new love lest I make a misstep and drown.

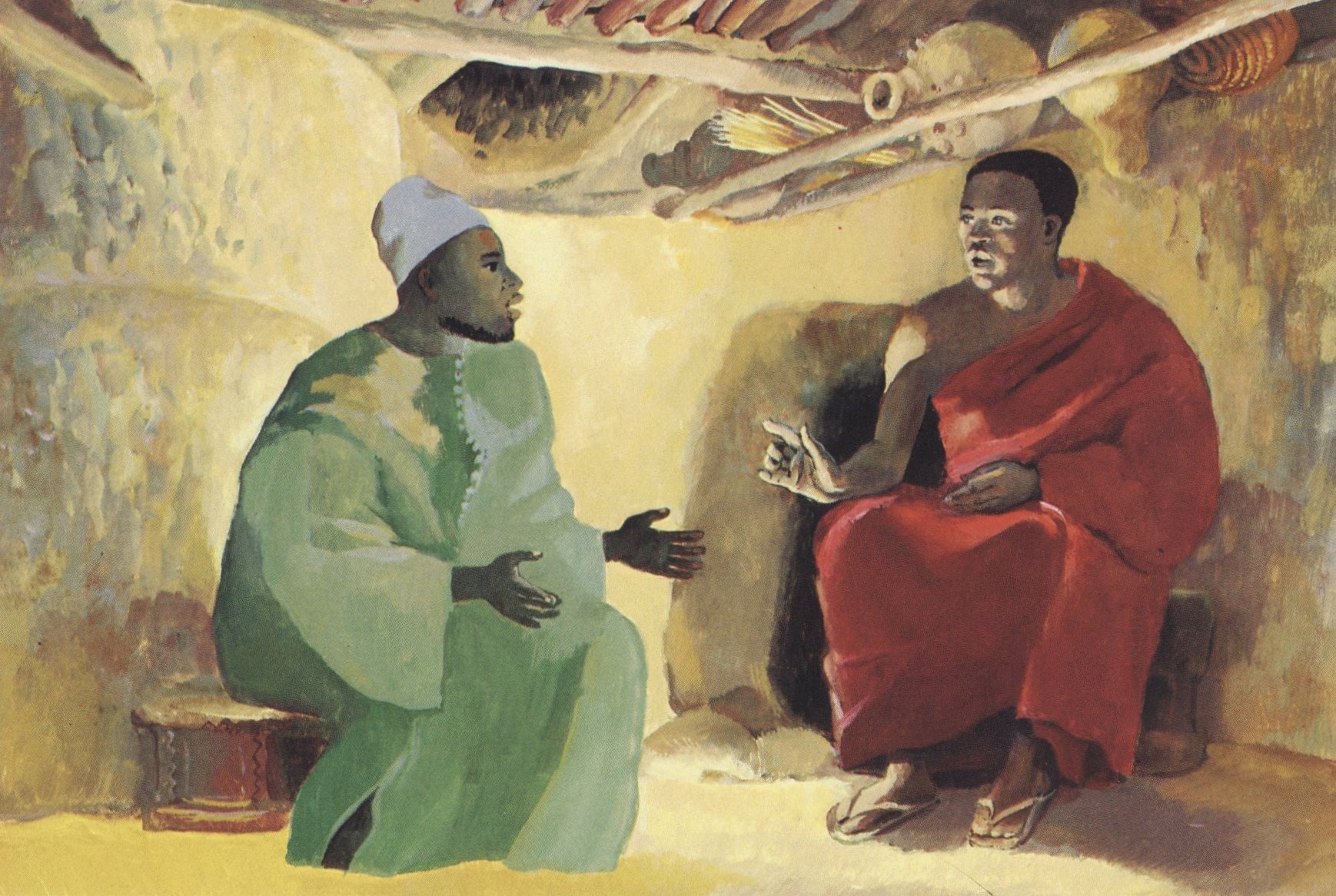

Instead of sitting in judgement of Nicodemus, I found myself sitting with him, as inquisitive as he was; as interested in Jesus’ message as he was; as unsure of what it all amounted to as he was.

As I put myself in Nicodemus’ shoes, I was drawn to the call that Jesus offered him. I found myself more entranced by Jesus than I’ve felt for years.

Mysterious calls

I began to see why the lectionary editors placed these two passages—God calling Abraham, and Jesus telling Nicodemus he must be born again—side by side.

God’s call to Abraham was mysterious.

God asked Abraham to leave everything behind, to start fresh. God did not tell Abraham where he would be going. God did not say how or when Abraham would be blessed, how or where a great nation would be made of him. Just that he needed to kick off a new life, to “begin again.”

And all that Abraham could lean on was the promise of a God who had been silent for generations.

Nicodemus felt the call of Jesus.

When Nicodemus investigated that, Jesus offered only a mysterious invitation to something new.

It’s imprecise—no reasonable person could have experienced that moment, with the context Nicodemus had in that moment, and walked away knowing exactly what Jesus meant—just that Jesus offered something new.

Some movement of the Spirit that you can’t quite tell the direction of.

And while this passage doesn’t immediately describe Nicodemus saying yes, I simply have to assume he did, whether right away or after a little while longer.

You don’t buy 75 pounds of spices for someone you think is full of crock.

I also started thinking about what I do when I’m called to a mysterious “something new.”

The will to change

The psychologist Harriet Lerner says that there are only two things you can count on every human being to feel: the will to change, and fear of change. “It is the will to change,” Dr. Lerner says, “that motivates us to seek help. It is the fear of change that motivates us to resist the help we seek.”

I felt that as I studied this passage this week. I knew I needed renewal in my understanding. I had the will to change.

But there was something in me that was too afraid of actually starting fresh. Too nervous to give these authors a chance at convincing me of something. Too nervous to look beyond the authors I was used to reading.

I felt that when I came to KCC for the first time. I’ve told this story before, but the first time I came here it was somewhat begrudgingly.

For a number of reasons, I knew I couldn’t keep going to the church I was attending, but I wasn’t ready to give up the exclusionary practices I learned there.

I wasn’t ready to believe I could be loved and accepted by God.

All I knew was I needed something new, so I showed up and—as my therapist Dr. Al says, “did it scared.” I began again despite the unknown about what might happen next.

I feel that when I start dating someone new—eager to enter the joy of a new relationship, but sometimes too fearful to give up the baggage of the last relationship, tempted to project all my attachment issues onto the new partner.

I feel that when I think about the Lenten question for this week—“what in your life or in the world needs to ‘begin again’?”

Before I had done my reset with the passage, I thought that was a cute, fun, question. Just the right question to ask during Spring. Full of optimism about new beginnings. Kind of a little more positive than I’m used to seeing in lent, if I’m being honest.

And I still feel that way.

But I also feel, like maybe Nicodemus felt, more conscious of what might hold me back. More honest about the fear of change that might compete with my will to change.

What if the thing that needs to begin again is something that’s going a direction I kind of like, actually?

What if the thing that needs to be born again is something like the thing Jesus’ told the rich young ruler to do in the story we read a couple months ago: “sell all you have till all that’s left is the people around you.”

What if the new land God calls me to means leaving behind my nation, my extended family, my immediate family?

Don’t get me wrong; I still feel the Spirit’s call to the “something new.” I still am drawn in by the mystery.

But I must commit to “doing it scared.”

I will commit to choosing my sense of wonder over my fear of change.

And I’m curious if you’d be open to joining me in that—into leaning seeking out where a sense of wonder and mystery might lead us into the joy of new beginnings, even if it’s a little bit scary.

Amen.