A sermon on Job 12–13, accompanied by a piano-vocal arrangement of Job chapters 38 and 39, for Kensington Community Church, San Diego, CA.

The book of Job has something of a reputation for being a book about suffering, but I think that’s not quite fair—neither to Job nor to his eponymous book.

I can see why people think of Job and think of suffering. Suffering is both the inciting incident of Job and the setting for the rest of the book. I just don’t think it’s about suffering. I think it’s about prayer.

Here’s why.

No one really reads Job.

Job opens with a folk tale. That’s the part everyone remembers.

We meet Job, this absolute hero of a guy who’s always careful to avoid doing anything wrong and even makes sure his kids are always upright, too. (Take note of that part, it’ll be important later.)

Then we cut to a scene set in the courts of heaven, where we meet the Adversary—a “divine being” whose character is a lot like (but debatably maybe not actually) Satan. The Adversary has just come back to heaven after a trip around earth, and he starts chatting with God. God goes “Did you see Job while you were down there? He’s the best, right? He never complains, always does good, a real golden child.”

Then the Adversary says “Job is only a golden child because you treat him like one; take away his comfortable life and he’ll become as wicked as the rest of ‘em.”

So God says “no, no, no, he’s really a man after my own heart, trust me. Job loves me as his God so much that even if we had a spat, even if I took away everything he loves, he still would not curse me—he’d come to me, talk it out, restore our relationship.”

The Adversary pushes back, accusing God of being a little pollyannish. God, pretty much instantly, dares the Adversary to prove him wrong. “Go to earth, take away every good thing Job has, and see what he does next,” God says.

The Adversary, then, just ruins Job’s life. Job’s business is destroyed, his sons and daughters die, his wife dies. Everything that made his life worth envying is ripped away.

Then there’s a 40-chapter-long poem where Job cries a lot and people try to comfort him, but he still cries and cries and cries, until finally God puts him in his place. Then the folk tale narrator comes back to tell us everything ended happily ever after and Job got a new farm and a new family. Yay!

Or at least, that’s what you get when you read it like we usually do.

Most of us, we read that opening narrative in detail, then skim the poem for the most dramatic stuff, and then pay close attention again when it gets to the fairy-tale-ending.

And who can blame us—40 chapters of poetry? What is this, AP English?

But when we read Job that way, we’re ignoring the best part—the poem.

The poem.

Somewhere between a Socratic discourse and a poetic epic, the poem captures conversations between Job and his friends, and later God, about how the universe operates.

We start with Job venting to his friends. Job refuses to curse God for the bad things in his life. Instead, he curses himself, internalizing his pain.

Eliphaz

One of Job’s friends, Eliphaz, chimes in and… he kind of agrees!

Eliphaz frames it like a disagreement, but what he says is essentially “maybe you’re not such a bad guy or anything, but we’re all sinners, we’re all less than God.” He tells Job to turn to God and then his whole life will be restored.

Job replies: “c’mon man, I wanted sympathy, not a lecture.” Then he turns to God and says “hey man, what’d I ever do to you?!”

Bildad

And before anyone can stop to hear God’s reply, another friend, Bildad, pipes up: “God is a God of justice, Job,” he says. “Maybe you didn’t sin, but someone must have sinned to cause this. Maybe your sons?”

Job, very reasonably in my view, says “if that’s the case, God is destroying the blameless for the guilty. Is he just acting like a vengeful man? God, you made me, you gave me life and watched over my spirit ‘till now, why are you suddenly going away from me?” He goes on and on, at one point saying, “is my whole purpose in life to be your prey, hunted like a lion?” The man is clearly distraught, and so he does the devout thing with that distress: he tries, desperately, to talk to God about it.

Zophar

But before we can hear from God, another friend, Zophar, butts in.

Zophar takes a jab at how silly it is that Job thinks God cares about all his whining. One translation has him saying “must a loquacious person be right?” He then gives a little speech about how there’s two sides to every story, and Job might not realize he’s done anything wrong, but he must have sinned somehow. So Zophar offers Job the most predictably-pious solution one can imagine: “go search yourself, find your sin, confess it, then God will restore you.”

Job will have none of it

And then we get to the part that Jay just read for us.

Job replies:

“Indeed, you are the voice of all people, and wisdom will die with you.”

I read the tone there as kind of mocking, like “oh right guys, you know how God works better than anyone else, sure.”

Job gets upset with his friends and their advice. He’s upset that they keep cutting him off; keep acting like he’s silly for trying to talk to God about his pain.

“I have become a laughingstock to my friends—

‘One who calls to God and is answered,

blamelessly innocent’—a laughingstock.”

One interpreter renders that stanza as

“I’m ridiculed by my friends:

‘So that’s the man who had conversations with God!’”

Job says no, hush you guys. I insist on arguing with God.

But then the friends interrupt and start talking again, and neither Job nor the reader gets to hear from God.

That whole thing repeats three times, each friend restating literally the same case they made in the prior round just with like, slightly different wording. It’s exhausting to read, and I’m sure would be even more exhausting to live.

Then finally, in chapter 32, we get a small reprieve: a new friend arrives!

One last friend: Elihu

This guy named Elihu shows up! Finally a different voice!

But then he says “Job, you’re right, it’s not because of sin.”

And I imagine Job looking all kinds of confused at this point. He must be thinking something like, “I don’t care if you think I’m right! Hush! I just want to talk to God!”

But Elihu pays no mind and assures Job he’s probably really as good of a guy as he thinks he is. It’s actually that God only lets bad things happen to good people, this is a way of refining Job. It’s kind of a “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger,” speech… which is a little funny to read when you consider that like, sure, it didn’t kill Job, but is Elihu not remembering Job’s wife and children?

I read all of this can’t help but imagine like, things getting even worse, something happens to Job himself. Job ends up hospitalized, maybe he’s in a full body cast or something.

These four friends show up with flowers, but 5 minutes after they arrive they’re standing around Job’s hospital bed arguing about the purpose of Job’s pain while Job is doing his best to zone out, pressing the call button over and over, praying a nurse will bring a medication that can rescue him from the tragicomedy of his present life.

And all of the sudden, the nurse arrives:

Well, God arrives.

God speaks

After a full 6 chapters of Elihu saying “God will use your pain to make you a better person,” God says “enough!” and interrupts Elihu.

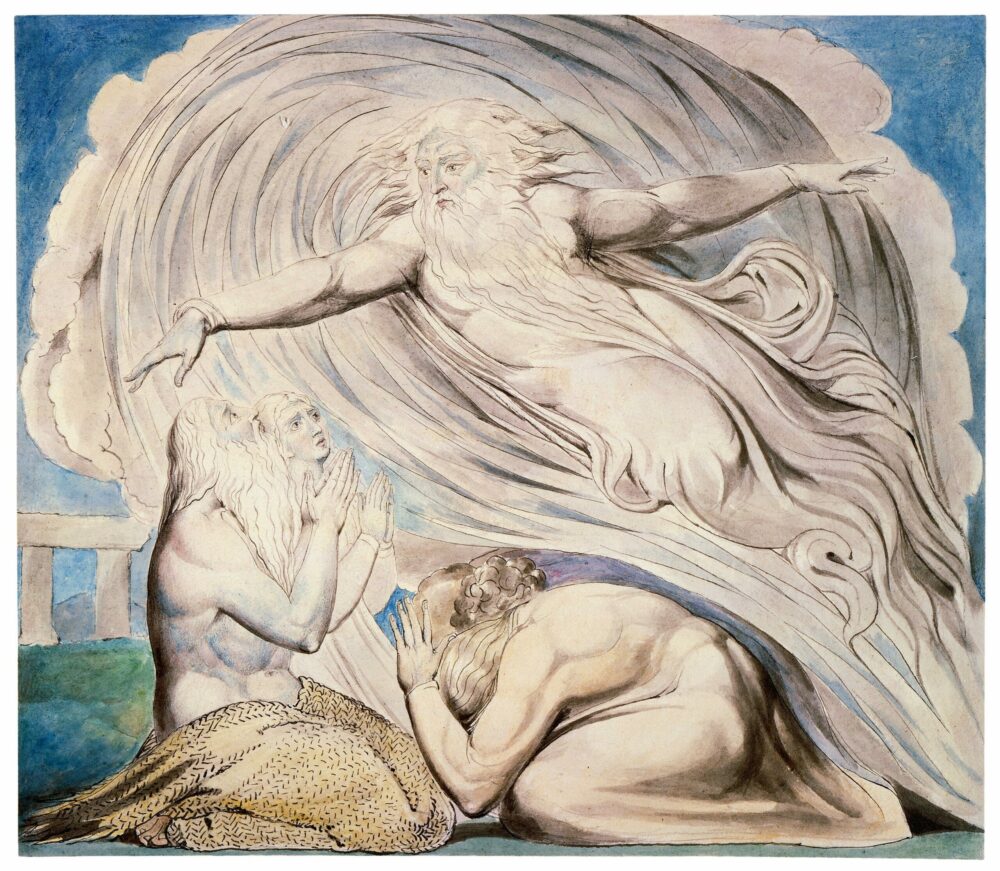

The scripture says the Lord appeared “out of a tempest” and said “Who is this … speaking without knowledge?”

And after putting Job’s friends in their place, God turns and insists on having the conversation with Job that Job has been asking for all along.

No more of anyone else speaking for God. It’s God’s turn.

And God’s voice is just so, so different than you would ever imagine if all you’d heard was the way Job’s friends talked about God.

God does not, at any point, blame Job for his suffering. God doesn’t blame Job’s children either, nor does God say “don’t worry, this is just to make you stronger.”

God doesn’t scold Job, calling him a “Karen” for wanting to “speak to the manager of the universe.”

In just two chapters, God takes Job on a journey through time and space, showing Job the world from a God’s eye view.

It’s the part of the book that you just heard David sing—that song is mostly just an arrangement of Job chapters 38 and 39.

“Where were you?,” God says.

“Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth?”

“Do you know who it is that set the boundaries of the sea?”

“Can you send lightning out on a mission, and have it respond ‘I’m ready, sir?’”

Hebrew scholars disagree about the tone intended in this portion of the poem—and who can blame them, right? It can be hard to decipher intended tone in an email that was written like, minutes before you read it; how much harder must it be to decipher intended tone in a text that’s been baking for the past 2,500 to 3,000 years?

The first time I read this part of Job, and I mean really read it, I heard God as something like a chiding parent, saying “don’t you know I know better than you?”

But the more I read Job, and the more I study the Bible, the more I’m convinced something else is going on.

I don’t think God is chiding Job; I think God’s taking Job seriously.

Job has long been desperate for something more than platitudes. He’s surrounded by people talking about God as an inaccessible dog trainer in the sky, rewarding good and punishing bad, and he insists that this is not the God he knows.

He insists on talking with and not just about God…

and God says “yes.”

God’s tone moves between gentle and caring, then transitions to a little bit annoyed that Job isn’t quite getting just how different things look from God’s eyes, and even, at times, to scolding Job for not trusting that God will be kind to him. As God is talking, you can hear this overwhelming sense of responsibility and power and seriousness.

God invites Job to a conversation where God does not dumb things down.

And only then, only after Job actually gets to talk with God, does Job feel comfort. Only then do things get better for Job, and only then do we see Job start to live into his happily-ever-after.

What I think is most interesting about that, is that it’s not even like God actually answered the questions Job brought to him. God does not say why all this pain was permitted—even if we, the readers, know something is up there.

But what God does say is that the God of real relationship has far, far more to offer than these theologizing friends who are trying way too hard to make things make sense. That God will not abide by simple answers. That God almost seems to want to fight about it.

God says “here, see, this is what things look like from my view;” God offers perspective to Job.

And I think that’s maybe even better than if God tried to give Job a tidy answer.

My prayer habits

When I started the discernment process—the journey towards ordination—I told my discernment mentor that I thought my biggest area for spiritual growth was prayer. That my prayer life had really tapered off over the past 7 or 8 years.

You see, when I was younger, I prayed a lot.

From the time I was like, 12 or 13 years old until I was 22, I spent hours every day praying that God would “cure” my homosexuality. I spent a decade in a self-imposed earthly purgatory, begging God to fix me; asking God why God would make me like men.

(I still ask that, for the record—just now it’s because I’ve spent years dating men.)

But anyways. I prayed, a lot. In the morning, at lunch, after school, after my after-school job. I’d journal my prayers, filling up a moleskin like this one every couple of weeks with desperate pleas to the God of the universe, asking him to make me have just one crush on a girl.

In college, the dining hall staff knew me as the first person to get to breakfast and the last person to leave. I’d wake up at 5am, go pray in nature for hours, then grab breakfast at 7:30am and spend three hours journaling and praying until the dining hall closed at 10:30.

I prayed that God would “shatter my dreams,” that God would “liberate me from my rebellious desires,” that God would “remove the thorn from my side.” But God refused to grant my wish. How dare God?

Like Job, I went to friends, and shared my burdens with them, I prayed with them. They’d give me advice for solving my “problem”—much of it well-intended; all of it ultimately very harmful. Still, no straight Stephen. How dare God?

Only years later, when I learned to make the world around me silent, could I hear God tell me that dishonesty, not homosexuality, was the thing I should worry about—that I had to stop pretending to be someone I wasn’t, I had to stop pretending to be straight, putting a veil over who God created me to be.

I wasn’t distressed because I was gay. I was distressed because I was trying to fake straight.

But I couldn’t hear that if all I was saying was “God please help me to have terrible taste in accessories,” and all my friends were saying “here’s a book that’ll help!”

God bless Gina —or— Talk less; listen more

If you fast-forward a number of years, after coming out, those hours-a-day-prayer sessions stopped.

I no longer needed to beg God to do a thing that God simply would not do—and I say “would not” on purpose: I do not care about if God can or can’t do it; I care that it’s not happening.

So I, like Job at the end of his book—and at the end of David’s song—fell silent.

Things built back up over time, but you can imagine why, with all that praying I did when I was younger, my current prayer life of like, blessings before meals and praying for my sick godmother, felt kind of… boring. Why, I’ve had my this one for 3 months now and it’s not even halfway full. And most of even that’s just to do lists!

But maybe, maybe what I thought was a lovely rhythm of prayer before, wasn’t actually so.

Maybe I, like Job, didn’t hear anything because I was too busy alternating between using my voice and hearing the voice of people who were actually just like, really not the right people to give advice on this kind of a thing.

Maybe I needed to put down my pen and paper, sit quiet, and listen?

Also, maybe I needed to start therapy a lot sooner than I did.

See, the “stop talking and sit with silence” thing is something Gina, my first therapist, taught me.

When we started meeting, I would show up to Gina’s office a few blocks from my college, babble on for 49 minutes about how terrible of a sinner I was, or how the root of all my problems was the gay thing, or whatever else, and she would just…

she would just sit there, receiving all of it.

Then when I finally ran out of air, she’d sit still as a rock, waiting for the room to fill back up with oxygen before saying like, four perfect words, then sending me out to her receptionist to book my next appointment.

It took an eternity of sessions like that before we could actually start problem-solving.

Bless that woman for her patience; she retired within a month of my “graduation” from therapy and I’m certain that’s no coincidence.

But during that time, in that silence, and even in her brief parting words, I was learning.

Gina, even if unintentionally, taught me a new way to pray.

Amidst the cacophony of my cries for help competing with the shouts of unqualified lifeguards trying to save me, Gina taught me how to pause and receive. Not to receive information, or guidance, or whatever, but to receive perspective.

Gina’s parting words were never like, tactical.

They weren’t things like “remember to complete that workbook before our next session.”

They were things like “that’s not true, is it?” or “you are not a bad person.”

They were gifts of perspective—letting me see my situation from her perspective. From an outside perspective.

Almost like Job getting to see things from God’s perspective.

God and us

While I could certainly still stand to invest a little more in my rhythms of prayer, after reflecting on Job, and thinking about the things I learned from Gina,

I think maybe what I thought was a loss in my prayer habit was a realignment—even a growth—in my prayer habit.

Job is not a book of tidy resolutions for people in pain. If you’re looking for guidance in suffering, it is—at best—unsatisfying. It is not a book therapists should recommend to help you explore the stages of grief.

But it is a book about the relationship between God and us—and not just a corporate “us,” but each of us as individuals.

Job is a book about the perspective we get when we engage with God sincerely; when we shout our real questions out load and then open ourselves up to the silence that’s required for the two-way conversation.

When we speak with and not just to or about, God.

When we pray. Job is about prayer.