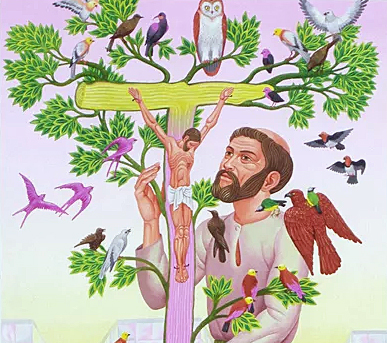

A sermon on Isaiah 11.1–9, for the Blessing of the Animals at Kensington Community Church, San Diego, CA.

In the beginning

The passage that Jim just read for us is out of the prophesy of Isaiah, it’s a vision the prophet has of a future peaceful kingdom. It’s a beautiful, poetic telling of what the world is like when everything is at peace, humans and animals all living in harmony.

But before we can get to talking about that, we’ve got to talk about the first time animals show up in the Bible: in Genesis 1.

If you, by some stroke of luck, are not familiar with the creation legend told in Genesis, here’s a quick run-down:

In the beginning, God created everything.

God made sky and water and earth and heaven and birds and fish and beasts and creeping things and plants and called all of it good. Then, to top it all off, God made humans. God said “let us make humankind in our image, after our likeness, and they shall rule the fish of the sea, the birds of the sky, the cattle, the whole earth, and all the the creeping things that creep on the earth.”

God says “just like I rule the earth, I want these humans to rule it.” God names humans like, Assistant Regional Managers of the planet. And of course, since we’re only Assistant Regional Managers, there’s a special limitation there: we can’t do whatever we want. Hebrew scholar Nahum M. Sarna describes this as an appointment of care on God’s behalf, like the Israelite kings—accountable to the people and to God for the way that we rule.

A few verses later, God sits the first human—who we traditionally name Adam, though it should be said that the scripture there doesn’t necessarily reveal the gender or name of that character—God sits that human down and brings every animal up to the human, one-by-one to name each of them.

Imagine you’re hanging out in your garden one day and a forty-foot-long twelve-foot-tall scaley thing with short arms appears, God asks you what you want to call it, and you’re like… uh, T-Rex. And then a 600-pound, 7-foot-tall beast appears, you hear it growl, and decide it’s a Grizzly Bear. I would run out of names so fast.

But there’s something else special that happens there, if you think about it: all these animals that we might think of as a danger to humans—lions, tigers, bears, the whole lot—they all are just walking around with the first human, at peace, like it’s no big deal.

It’s this idyllic, peaceful, harmonious scene, where everyone is interdependent on one another, and the first humans are gentle stewards of all that God has given.

Then, a disruption happens.

The end of peace

The second human ever created is walking in the garden, and a serpent appears. The serpent says “break the one rule God gave you, and you will ascend to a higher plane—you won’t just be made in God’s image, you will be equal with God.” “Here’s how you get promoted from Assistant Regional Manager to just-plain Regional Manager.”

No more need to be a gentle steward on God’s behalf anymore; you can run the show, do things how you want, treat the world how you want. “And just wait until you find out about the oil reserves in Texas; you’re gonna love running that show.”

The second human gives in to temptation, and then… everything falls apart.

They tried to move from “steward of the world” to “ruler without limits,” and now conflict, the whole concept of things not being at peace has entered the world for the very. first. time.

God comes down and says “oh man, y’all messed this one up. Look, I’m going to keep taking care of you. But now that conflict is here, things aren’t automatic. You’re going to have to work the land, tend the cattle. You’re going to experience pain. Peace has been broken, and healing broken peace takes work. You tried to dominate the animals and plants and even other humans, and they’re not going to just go along with you anymore.”

No more swimming with the sharks, they fear us and we fear them, now.

No more hanging out with lions, tigers, and bears. Their grizzly teeth are a risk to us.

And at least some scholars think that this moment, the move from “all at peace, human and animals hang out in harmony” to “conflict is now present,” is something the prophet Isaiah had in mind when he wrote the scriptures that Jim read for us.

The peaceful kingdom

When Isaiah wrote this prophecy—well, when he probably wrote it; dating things this old is a little hard—the Kingdom of Israel had been destroyed in a brutal war by the Assyrians, and the Israelites are wandering the desert in exile.

Isaiah is envisioning a time when the “shoot of the stump of Jesse”—a king descended from David; a king anointed by God—rules again. An Israelite king, ruling the Israelite people just like God told humankind to rule the world.

This vision is something that, a thousand-or-so years later, early Christians would look at and go “hey, that king is Jesus; Jesus descended from the line of David; Jesus brings peace.”

But whether you believe this to be about a human Davidic king or whether you apply this to Jesus, when that kind of rule happens—when things are done God’s way; when we’re stewards not boundless rulers—everything is at peace again.

In that peaceful kingdom, all judges judge with equity, and the lowly are given justice.

Leopards and wolves lay down with goats and lambs, they don’t hunt anymore.

The calf and the beast of prey lay down together.

And a young child leads them around.

Babies play with snakes, and nothing happens to ‘em because conflict isn’t a thing. All is at peace.

Every creature has what they need without needing to compete.

When I hear all of that, I can’t help but think about the little beasts we live with nowadays as maybe a glimmer of that peaceful kingdom.

The beasts that we live with

The story of animal domestication is complicated and varies by species, but one of the most common narratives goes something like this: humans were traveling around, hunting and gathering. As they travelled around, they brought food with them. That food attracted yet-to-be-domesticated species (the ancestors to dogs, for example, were probably attracted to meat around the fire) or maybe it attracted species that attracted those species—grain that humans collected probably attracted mice that probably attracted cats, for example.

The more hostile representatives of each species got shooed away by the humans, but the more friendly representatives—we let them come around, maybe even tossed them a bone or two as we finished off our meals. And we started to realize that if we were kind to these animals, they would be kind back.

If we let cats hang around and didn’t complain if they stole a little grain, they’d keep the bulk of our grain free from pests. And it didn’t hurt that they were cute to look at.

If we let the proto-wolves hang around, they’d treat us like a part of their pack, protect us from bears, and some of them even had special talents to help us when we were hunting.

Somehow, those protective instincts got lost on every dog I’ve ever owned. But I’ll have to find a way to forgive them for it.

Because those relationships grew from practical evolutionary tool to genuine companionship that was both mutually beneficial and deeply personal. The first evidence of humans holding funerals for pet cats is from around 7,000 BCE.

And in many ways, those relationships of mutual care and companionship aren’t too different now.

I think about the herding dogs, descendants of wolves, now quite literally lying down with lambs.

I think about this veteran I know with a service dog that helps him manage PTSD symptoms—a creature with big ol’ K9 teeth bringing peace to a soul harmed by conflict. The same animal is eternally gentle with his young children.

I think about all the furry mutts folks adopted near the start of the COVID pandemic; how they brought companionship to so many folks getting much less social connection than we were used to.

I think about the cat who brought playfulness and life into the home of a friend when he was living alone for the first time after a decade-long marriage ended in a painful divorce.

The pets we live with are gifts from God, and, if we care for them the same way God would—the way that God charged us to care for all creatures in Genesis 1; the way Isaiah envisioned the God-anointed ruler would care for Israel—they can give us a glimpse, a model, of the peaceful kingdom God calls us to bring on earth.

Amen.