A sermon on Luke 11:49-52 and 18:1-8, for Kensington Community Church in San Diego, CA, shared the Sunday after the overturning of Roe vs Wade as a part of a service of lament.

Jesus, please wash your hands

Each of the gospels–Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John–have their own way of telling the story of Jesus. The author of Luke gave us a literary epic. We get the whole story of Jesus, from birth to resurrection, with a big chunk in the middle that is focused on Jesus’ public teachings. Luke spends 60% of his gospel on just 6 months of Jesus’ 33-ish year life, but that 60% is just jam-packed with didactic dialogue, parables, and sermons.

Our first reading today, from Luke 11, shows up towards the start of that 60%.

Jesus has been invited over to dinner with some of the Pharisees, the religious leaders, and he neglects to wash his hands before eating—something which has ritual significance for the leaders in question, but also, like… Jesus please wash your hands.

Anyways, Jesus forgets to wash his hands, and these religious leaders very gently mention it to him, and this gentle call out gets Jesus going on an absolute rant about why religious leaders are the worst, and all hypocrites, every last one of them. This reading shows up at the end of that rant; Jesus has been railing on the Pharisees for goodness knows how long, and a lawyer pops up and says “hey dude, when you rag on people who care about doing things the right way, you’re offending us lawyers, too.”

And Jesus hits back with “you bet I am,” the passage we just read.

“You load people with burdens too hard to bear, and you do not lift a finger to ease them.”

“You have taken away the key of knowledge; you did not enter yourselves, and you hindered those who were entering.” That knowledge stuff is something Matthew, in his account, remembers as the Kingdom of Heaven. You have hindered those who were entering God’s Kingdom, Jesus says.

A note on antisemitism

I do want to note, before we go any further, that this passage is the one I was talking about in that before we began the readings for the day, the passage that Christians have used to fuel antisemitism in the past and, I say this with deep regret, still today. It happens on purpose, but it also happens—in congregations just like ours—on accident, all the time. The “Pharisees” Jesus is bickering with in the gospels are the fathers of modern-day Judaism. It doesn’t take a lot of logical leaps to read this and go “Jesus fought with the leaders of Judaism, so Jesus must be anti-Jewish, so [insert excuse for atrocity here].” To that, I will remind us of three things.

- Jesus was Jewish. Jesus was not an outsider haranguing Jewish religion. He was an insider providing internal critique. There are plenty of examples throughout scripture of Jesus concurring with and learning from the Pharisees, and of Pharisees who were close friends of Jesus—the tomb Jesus was buried in is a burial plot that had belonged to a Pharisee, who donated it to Jesus so he could have a dignified resting place. A Christian taking this as license to antisemitism would be like a cis straight guy taking internal fights about how Pride can be even more inclusive as license to be homophobic. Nonsense.

- The genre of the gospels is gospel—it is its own genre. These are confessional texts, not historical ones. That does not mean they have no historical use, but it does mean that the authors of the gospels were not trying to write “history.” They weren’t attempting to be journalists, composing an objective perspective of the experiences of the Nazarene Zealot as they happened in real-time. They were early Christians telling these stories as they remembered them, documenting oral traditions just shy of a century after the events described actually happened. And in that century, followers of Jesus went from being a sort of fringe movement within Judaism to a religion of their own—Christianity. Along the way, there was a lot of fighting. That fighting was complicated by the influence of a cruel Roman Empire that did everything it could to divide the people they colonized, and it was complicated by Christians who chose to ally with the empire over the Jewish people. You can imagine what that can do to the way you color your memory of events.

- We must interpret Jesus in his totality. The same Jesus that we’re told was fighting with the Pharisees was also telling us how our job is to love our enemies. To the extent that the Pharisees and Jesus were oppositional, it would require a great deal of inconsistency for Jesus to intend anything even approximating the hatred that leads to contemporary antisemitism.

Android phones and judges

Now, our second passage.

That one is a parable, and it shows up close to the end of that “60% of Luke that’s all the teachings of Jesus.” We enter this story in the middle of a dialogue Jesus is having about the Kingdom of Heaven. There’s an academic name for this type of parable, but it’s in latin and I’m scared to mispronounce it, so I’ll just say it’s a “how much more” kind of parable. “If the crappy version of this thing can find a way to be good, then the perfect, God-run version of that thing? It must be great.” It’s sort of like how this website developer I’m working with at my day job designs websites with like, duct-taped-together 10-year-old Android smartphones in mind. “If it can work there, it’ll run great on a desktop or on a new iPhone.” (Sorry, green text message crew).

Anyways, in this case, Jesus is saying “you can protest against an unjust judge until he relents and does the right thing. God is a just judge, and in the place where God rules, in the Kingdom of Heaven, justice comes the moment you ask for it.”

When Jesus talks about the Kingdom of Heaven, he is talking about a place where God, not Cesar, reigns, and that means’ God’s laws—the law that Jesus called “good news to the poor,” “sight to the blind,” “freedom to captives,” the law that says “the first are last,” the laws that fill the hungry with good things and leaves the rich to their own devices—those laws run things in the Kingdom of Heaven.

And when early Christians talked about “King Jesus,” or prayed “Come, O King,” they weren’t saying—or at least, weren’t intending to say—“we believe it is a good thing to have kings; we believe in absolute monarchies.” They were maybe even saying the exact opposite—they were saying “we need the righteous king to come replace the evil rulers of our world.” When we sang that song with the refrain “He is God,” we were not saying “men are God” we were saying “one, specific man, Jesus, the man who is like us, who bore the cross in solidarity with human suffering, is God. Our God is the God who suffers with us.”

We can tell this is true, in part, by the parable itself. In this parable, the assumed context is that absolute rulers—judges who can unilaterally decide whether a widow gets relief from “the accuser” (a word that is potentially an allusion to a label for the devil) exist. Judges who neither fear God nor respect people. Some old latin translations used to render this as “despising” the “vox Dei” or “voice of God” and the “vox populi” or “voice of the people.”

It’s a good thing we don’t have judges like that anymore, right?

But anyways, my point is that Jesus is clearly speaking to an audience who knows what it’s like to be the character in the parable. Jesus is speaking to an oppressed people and saying “there is a place, a place where God himself has taken the place of those unjust judges, and everything is so much better.”

And throughout the gospels, we see Jesus inviting people to that kingdom, telling the powerful to repent—to turn—from their abusive ways and choose instead a world without hierarchies. Telling the outcast that this is a kingdom for them. It is something that, as Jesus mentions just a few verses before our second reading begins, is as much cosmic as it is earthly: it is a Kingdom of Heaven, and it is on earth as much as it is in heaven.

Christ the redeemer

That’s also a lot like what we’re talking about when we talk about God as a redeemer. A redeemer, in the legal system of first-century Palestine, was someone who bought freedom for a captive–for someone who was an indentured servant or a slave.

One way that people think about what Jesus’ death and resurrection means—and in fact, probably the oldest way of thinking about it—is through a framework called “redeemer” or “Christus victor” theory.

The narrative goes something like this:

There is a power of evil that has held earth captive. Throughout scripture, that power is called a few different things–the deceiver, the accuser, ha’Satan, you get the point. This power of evil rules with an iron fist, corrupting humanity and causing death, everywhere, violence left and right.

God saw that and was furious. God made people in God’s image, people are God’s children. This was an affront to God.

God sent the prophets to rip that evil to shreds. They proclaimed all these evil things, all the ways evil has convinced us to harm one another, as sin, as haram, or “under the ban.” Satan and his evil ways were banned by God.

But evil kept winning.

So God said “I will march right down there and face Satan head-on.”

God, then, shows up on earth as the “illegitimate” child of a teenager from a poor slum. God, in Jesus, experiences some of the worst that these evil powers can deal out. But he won’t relent. He walks around saying “evil doesn’t have to win!” “God is more powerful, God is a just King, and his kingdom is coming! Just you watch.”

That makes the forces of evil–the Roman Empire and/or Satan–absolutely furious. They say “death it is,” and sentence Jesus–sentence God–to execution.

And for a moment, it looks like it works. It looks like evil has won.

But then, in a stunning rebuke of those evil powers, Jesus rises from the grave. Jesus proves that God really is stronger than the worst that Satan can dish out. God has won the war against Satan.

And even though evil won’t quite accept defeat, even though we still inhabit a world where evil exercises itself, we are not captive to it. With each battle, the Kingdom of Heaven–where the last are first and the lost are found–is getting one step closer to totally realizing its legitimate reign. The people who were captive to the evil one have won their freedom, it’s been bought for them, even if it’s not fully realized yet. Our freedom may not be completely operational yet, but it’s also not exclusively aspirational.

The “s” word

I will not pretend that narrative is totally satisfying to me, for the record. I struggle with it. I like the idea there, but… but it’s hard to latch onto in a world where evil seems to keep winning victories.

But it’s the best I’ve got.

And it’s why I won’t give up the “s” word: “sin.”

I know, intimately, how much the word “sin” can be used for harm. I spent most of my life surrounded by people telling me I was a walking sin. When I was first diagnosed with HIV/AIDS, I had it real bad, so I was hospitalized for a bit. Somehow, folks I knew from a former, more fundamentalist life had gotten word, and when I arrived home, I came home to a mailbox with cards and letters telling me my disease was punishment for my “sin” of homosexuality, and God would heal me if I only stopped loving men.

Which, by the way, if that worked, someone would have patented it and started making billions already. Find a way to simultaneously cure AIDS and make me not attracted to men of all people, yes please?

But I say all that to say, I know “sin” is a dangerous word. I know enough of you well enough to know that you have stories just like mine, stories that can make “sin” a little bit of a trigger word. And so I try to be careful about how and when I use it. have edited liturgy so that it says “where we wrong” rather than “where we sin,” specifically so we can focus on the thing we need to focus on, rather than focusing on the baggage that comes with the word “sin.” I gently adjust old hymn lyrics before they make it into your bulletin, careful to keep them from bringing baggage our worship services do not need.

But if I don’t have the language of “sin” at all, I don’t know how else to explain why we hurt one another, why the world is not as it should be.

I don’t know how else to describe the fact that people were buying Hallmark cards and postage stamps to send actual hate mail in the year of our Lord, 2017. Send me an email!

But I digress.

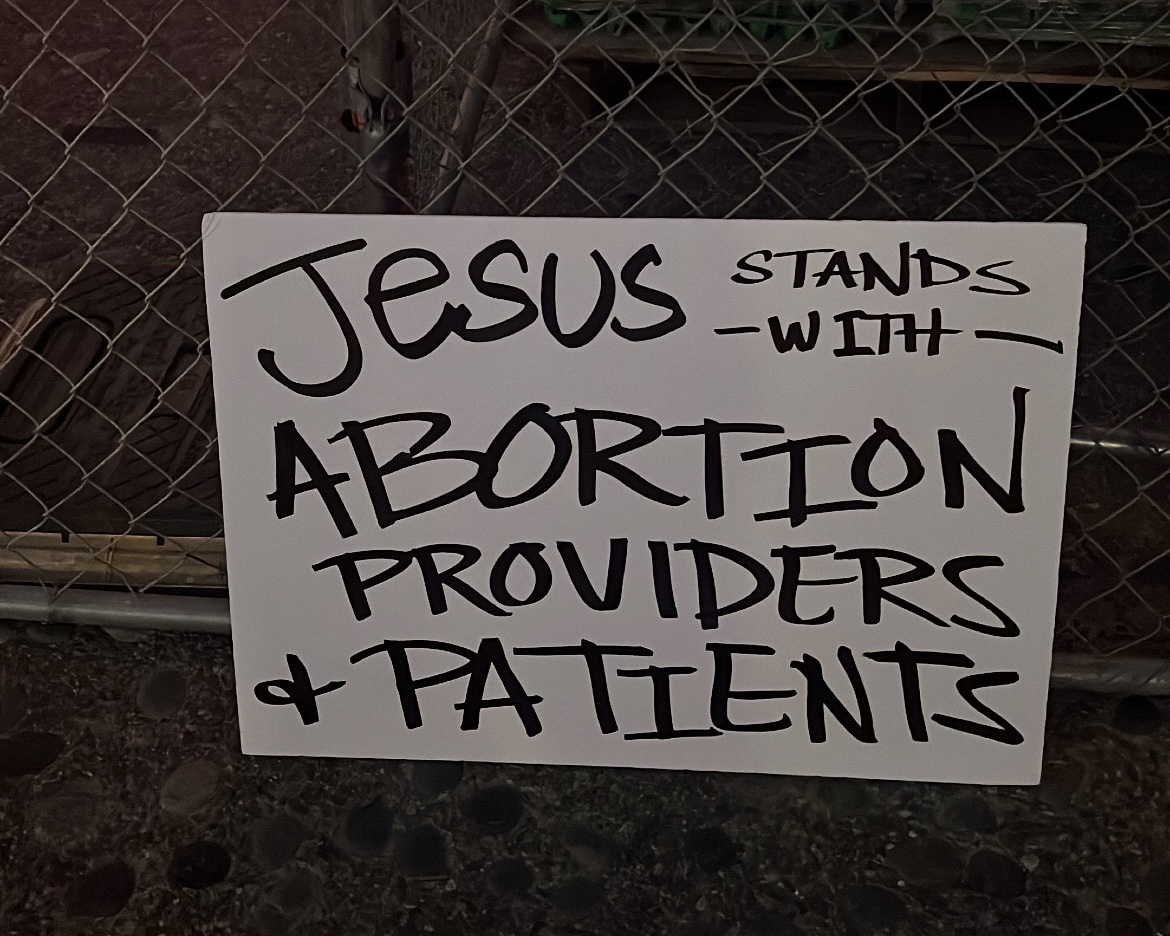

If I am to believe in a loving God while living in a world where our judges protect potential future children more than the children living with us right now, in a world where women are obligated to carry out the State’s will, even at grave harm to their health and life, I have to at least have a category for things God has put “under the ban.” Things that God has said God will not tolerate.

And I have to trust that God is joining me, is joining us, in solidarity in a fight against that kind of evil. I have to have hope that if we keep fighting, if we keep begging the unjust judge for justice, he will relent and start operating like the righteous judges in the Kingdom of Heaven do.

And honestly, I don’t much care if I’m wrong to hope for that, to fight for the cause of the Kingdom of Heaven, imagining there will come a day where only righteous judges rule.

I would rather hope in that and be wrong, than reject the hope and be right.