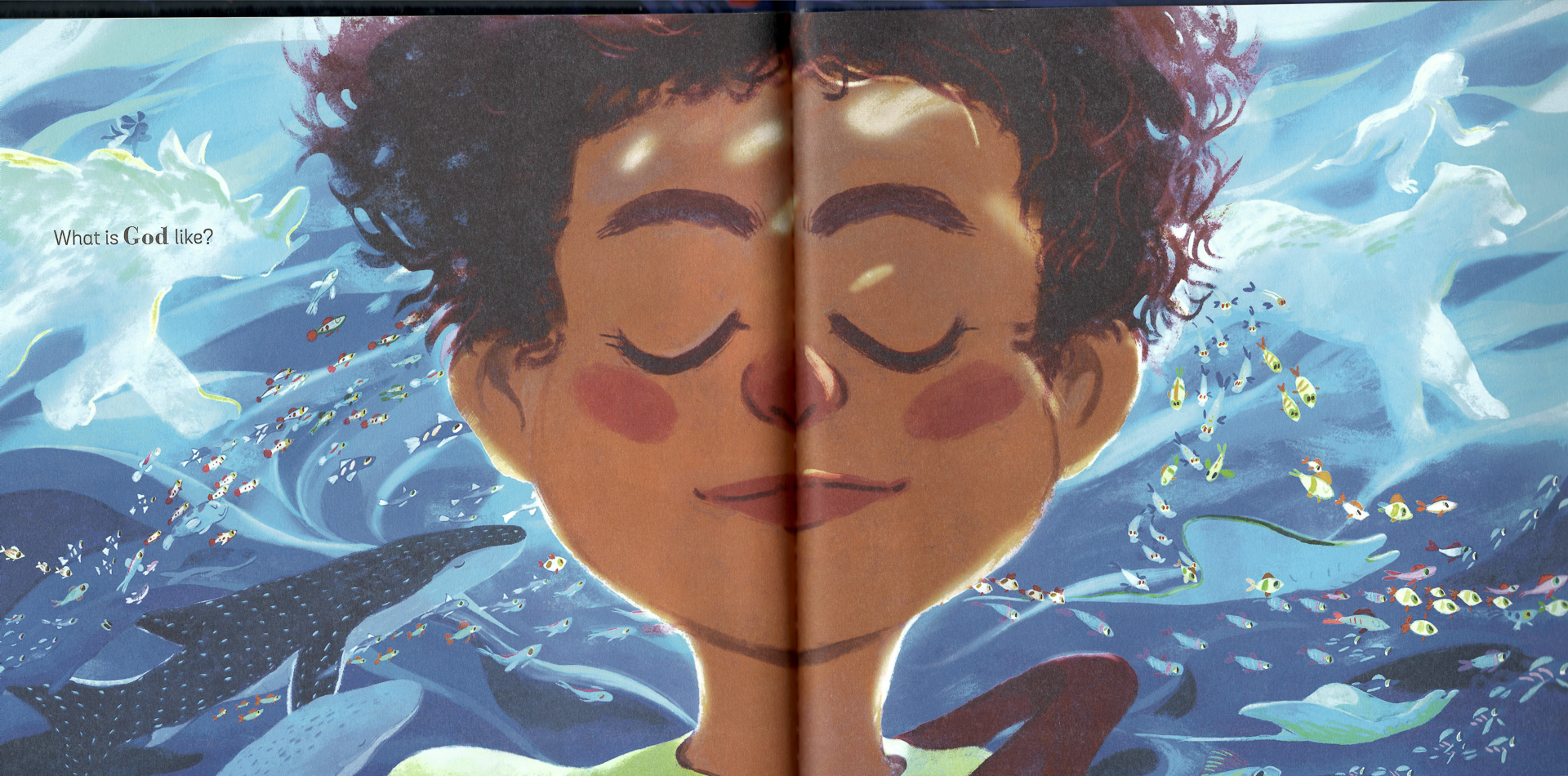

A sermon on Matthew 28:16–20 and 2 Peter 1:16–18, for The Table United Church of Christ in La Mesa, California on the occasion of Trinity Sunday. Originally accompanied by a reading of Matthew Paul Turner & Rachel Held Evans’ children’s book, What is God Like?

I mentioned at the start of service that I can sometimes find Trinity Sunday a little bit annoying.

It’s a tough Sunday to be the preacher.

I was a bit ashamed of this—ashamed of having a hard time planning this service—and then I went on Twitter and saw all my clergy friends griping about how hard it is to preach today, too.

And if I’m honest, that’s not just a gripe I have with Trinity Sunday. No, on deeper introspection, I think I have to confess that I have a hard time with trinitarian theology. Or at least with having to be the one to teach it.

It’s hard to wrap your mind around!

Every time I feel like I understand the trinity, I realize I messed up a big part of it.

The trinity is simple

But even in my own failure to comprehend the trinity, I have been assured—many times—that the trinity is actually quite simple.

That you just have to remember the Athanasian creed:

We worship one God in trinity, and the trinity in unity

neither blending their persons

nor dividing their essence

For the Father is a distinct person,

The person of the Son is another,

and that of the Holy Spirit still another

But the divinity of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit is one,

their glory equal, their majesty coeternal

Easy, right?

Oh that doesn’t work for you? Just remember St Augustine’s propositions on the trinity.

There is only one God

The Father is God

The Son is God

The Holy Spirit is God

The Father is neither the Son nor the Holy Spirit

The Son is neither the Holy Spirit nor the Father

The Holy Spirit is neither the Son nor the Father

Now, I’m not the most reasoned person you’ve ever met but I took high school geometry and I at least passed—even if barely—the section on mathematical proofs, so I know that is not how the transitive property works.

It’s like looking at an equation that’s all ones.

One plus one plus one equals… one?

One minus one minus one equals… one?

Even when you add in a 3, it doesn’t quite make sense. 3 divided by 1 is 1?

And anyways, when there are more propositions to your logic than there are fingers to count on, I think you don’t get to call things simple anymore.

“That’s modalism, Patrick!”

Maybe an analogy will help me understand.

But the first thing you learn when you go to find analogies about the trinity is that they’re all heretical.

There’s this hilarious YouTube video put out by a Lutheran comedian, in which Saint Patrick tries desperately to explain the trinity to Irish peasants, but they just keep calling him a heretic.

He offers that the trinity like an egg: egg white, egg yolk, shell; distinct in their own way, but all one egg.

“That’s modalism, Patrick!” the Irish peasants assure him. It acts like the persons of God are separate, fractional, incomplete. But each person of the trinity is fully God.

Maybe the trinity is like water–one substance in three states: solid, liquid, gas.

That, too, is modalism, Patrick!

See the problem is that no one molecule of water can be all three states at once—it can’t simultaneously be solid, liquid and gas the way that God can simultaneously be Christ, Creator, Companion. And God is not one person in three forms, like water moves through, God is three persons one God.

Well that’s partialism, Patrick!

The three leafs are distinct things; without one another, they are not the clover. But that is not true of God. God is fully present in Jesus Christ, in the Holy Spirit, and the Father.

Maybe the trinity is like the sun: simultaneously star, light, and heat?

Congratulations, you’ve committed the heresy of Arianism! The light is not the sun, it just emanates the sun; so, too, the heat is not the sun, it just emanates from the sun. This analogy would imply Jesus and the Holy Spirit are somehow lesser than God, sent from God but not themselves God.

Some say that the trinity is like a person who shows up differently in different contexts – like how to some I’m a minister, to some I’m coworker, and to others I’m a brother or uncle or son.

Welcome back to modalism, Patrick! Denying that God is all things at once, not three distinct things in three distinct places, the way I switch from minister to coworker when I take off my collar and get on a zoom call.

It can be, as a student of theology, really frustrating.

Almost like it’s impossible to contain God!

Can the good people who wrote the RCL help us?

Well maybe today’s texts, selected by a committee of theologians from nearly every Christian denomination for us to read on Trinity Sunday, can help us.

We start with a reading from Matthew.

The verses we read from Matthew are the very, very last verses in Matthew’s gospel. Jesus has died, resurrected, walked with the disciples. This is the story that, in other gospels, ends in Jesus’ ascension to heaven.

The eleven disciples—Judas is absent, for reasons you may recall from Holy Week—go up to the mountain with Jesus. They saw him and worshipped him… but, the scripture tells us, some doubted.

While the scripture isn’t specific about what they doubted, I can imagine it might be, I don’t know, that Jesus was resurrected and in front of them. That they weren’t just seeing things, that it wasn’t some post-traumatic hallucination of the loved one they lost.

Yes, and

If you’re paying close attention, you’ll notice two things about the narrative pretty quickly.

First: we see “they” worshipped him, but some doubted.

The word there that is translated as “but,” is a more neutral conjunction in the Biblical Greek. It’s often translated to “and,” and while I am not a scholar of Greek—while I do not know why the translators chose “but” here, even if I’m sure they had their reasons—I am still tempted to wonder if “and” is not the better translation.

There’s no indication here that a limited number of disciples worshipped Him. Only that a limited number of disciples doubted. It looks, to me, like the ones who doubted, doubted and still worshipped.

One of the reasons I think that might be the case, is the second thing that a close observer might notice about this narrative:

Jesus does not seem to care about the fact that some are doubting. It doesn’t seem to bother him.

Moving on…

This isn’t the story of Doubting Thomas, in which Jesus offers proof of what happened.

Jesus doesn’t stop and check for understanding of who he is, ensuring the disciples “get” the full picture before he leaves. He doesn’t go “hey, soon you’re going to be responsible for going out into the world and making disciples. You’re gonna need to know this stuff inside and out.”

He doesn’t make them recite the Athanasian creed before they’re commissioned to go out into all the world.

In fact, when I read this, I almost wonder if he’s trying to make it even more confusing. If he’s trying to say “oh only some of you doubt? Let me see if I can get all of you to!”

Because right after we’re told some doubted, Jesus offers what I see as an even more challenging proposition than the idea that Jesus was resurrected: that Jesus has all authority on earth and in heaven.”

Jesus is one-upping their doubts.

“Well, folks, it’s not just like I was resurrected by someone else. I’ve been resurrected because I have the authority to do that. I have authority over the laws of physics and reason and mathematical proofs. I am the author of creation and I will decide how the plot progresses.”

Surely, if I were a disciple who had not yet assented to the idea of resurrection, I would not have an easier time with the idea that my friend the working-class Zealot from Nazareth had power over all earth and heaven.

And after stumping them further, after challenging the disciples with an even grander view of who he is than just resurrected, he offers them what many call “the great commission.”

He sends them out, transforms them from disciple, a word that means something like “student” or “learner,” to apostles, a word that means something like “the sent-out ones.”

Jesus tells them to go into all the world, baptizing them in the name of this mysterious Father, Son, Holy Spirit thing, sharing the news of the upside-down first-are-last kingdom, of the man whose mother proclaimed in his conception that God had “cast the powerful down from their thrones and lift up the lowly,” “fill the hungry with good things and send the rich away empty.” They are given this commission, and then given a reminder:

Moving on… [together]

“I am with you always, even to the end of the age.”

Jesus offers them comfort in this mystery not by giving them answers, not by resolving the mysterious parts of the mystery, but by saying he’s not really leaving. At least, not in the way a human person leaves and is no longer accessible to us.

When Jesus leaves, God does not leave. God is still among the people. The disciples will receive the Holy Spirit. They have a continued advocate and teacher, a continued presence of the holy mystery.

Their learning isn’t over yet. Their seeking isn’t over yet. Their doubts don’t need to be resolved for their work to begin.

We can see that a bit, I think, in the reading from 2nd Peter. 2nd Peter is somewhere between a letter and a farewell speech—a “testament.” It’s one of the most recently-written books of Christian scriptures—so recent, in fact, that I should note some scholars doubt Peter himself could have written it at such an old age. Some think it’s maybe an early church “recollection” of Peter’s teachings and farewell speeches.

In this Testament, Peter offers a passionate defense for belief in Jesus and for obedience to holy scriptures. He’s got some language in his Testament that’s rather strong, telling folks that they can’t just go off believing anything.

But the most fascinating thing is that Peter doesn’t use reason for any of this. He uses an encounter. He says “I’ve seen this Jesus with my own eyes.” “I saw Jesus and I saw when the Holy Spirit descended from Heaven saying ‘this is my Son, my Beloved, in whom I am well-pleased.’”

It reminds me a little of when one of my seminary friends said that he “didn’t much care” whether folks left his church believing the resurrection. What mattered to him, he said, was that folks left having encountered the risen Christ. Having experienced the Jesus of scriptures regardless of their doubts, and having been renewed by that Jesus, transformed into someone whose approach to the world is entirely more loving and giving and sacrificial than could ever be imagined otherwise.

But enough with my friend who Peter maybe would or maybe wouldn’t have liked. Back to Matthew.

After we learn some disciples doubted, and after Jesus one-upped those doubts, and even without those doubts resolved, Jesus commissioned them to go out into the world, baptizing and making other disciples—other learners.

And while the insurgent Kingdom of Heaven that Jesus talked so much about isn’t mentioned here, in this command to baptism, Jesus is referencing something I can’t help but see as effectively the same thing.

Being made new

You see, while “baptism” “in the name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit” is a new invention of Christianity, the idea of baptism didn’t totally come out of thin air.

While we don’t have direct written documentation of this, all signs point to baptism being a Christian reinterpretation of the Jewish tradition of tevilah, a rite or ritual of washing in living waters of a mikveh. I should be clear that I am neither a scholar of comparative religion, nor Jewish—so take my understanding of Jewish tradition with a big grain of salt and talk to a Rabbi before you make too big of a conclusion from it. But from what I gather, the rite of tevilah has powerful symbolism in Judaism, representing for many Jewish people a sense of renewal, a sense of completion, a mark of transition, a start of something new.

Jesus, in referencing this ritual, is telling the disciples, “go out and offer to the world and offer renewal. Go out and offer them the things I’ve taught you that left you feeling renewed.”

I can’t help but wonder, friends, if the reason we can’t get away from the complexity of the trinity is that we are being called into the same.

We are being given the holy mystery of God, revealed in the scriptures that our forebearers have compiled out of six millenia spent triangulating who God is and what God is like,

So that we might be taught to be constant seekers, to be constant learners;

So that we might never be compelled to think we have all the answers, but instead to hope for all the right questions;

And so that we might instead be compelled to go out and humbly offer renewal to all the world around us.

Amen.